|

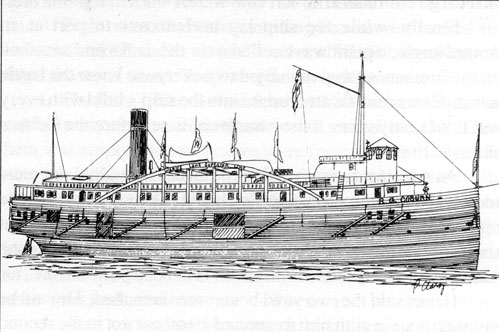

| R. G. Coburn |

From my book

Steaming Through Smoke and Fire 1871

Gilbert Demont's

Last Command

Capt. Gilbert Demont's only mark on history:

he was the master of the ill-fated propeller R. G. Coburn who bravely went down with his ship on stormy Lake Huron.

Beer's

History of the Great Lakes paints a romantic picture of Demont, standing just aft of the texas with his hand on the rail as

the Coburn made her final plunge.

Survivor accounts and government documents suggest that the glamorization of Demont

as a gallant sailor may not have been deserved. There is evidence that he was an incompetent and inexperienced mariner who

accidentally got his vessel in the middle of a killer storm and then didn't know what to do.

The record shows that

Gilbert temporarily replaced a retiring skipper and was only in command of the vessel until the Coburn reached Buffalo. That

his replacement, Capt. John Condon, was a passenger aboard the Coburn when it sank, is somewhat unexplained, however. When

the boat went down on Sunday, Oct. 15, 1871, it took 16 passengers and 15 members of the crew to the bottom with it. Condon

was among the survivors.

Peter J. Ralph, Eighth District Supervising Inspector of Steamships, suggested in his report

that Demont was negligent in the way he handled the ship.

"If the anchors had been let go, so as to have brought the

vessel's head to the wind, as the depth of the water in the locality of the disaster is only from 30 to 40 fathoms, and the

vessel having good anchors, with 90 fathoms of chains each, there is a probability that this loss of life and property might

have been lessened, if not entirely avoided," Ralph wrote.

He also reported that the Coburn was equipped with an adequate

number of lifeboats, and that everybody aboard the vessel might have escaped if the lifeboats had been properly managed.

"Two

metallic life boats were picked up on the Canada shore, right side up, which evidently were not used, except by two of the

crew, Porter and Barber, who were found dead on the beach where the boats came ashore. The eighteen survivors had the wooden

boats," Ralph noted.

Historians have attempted to link the disaster to the great forest fires that ravaged Michigan,

Wisconsin and northern Illinois the previous week. It is true that the smoke from the fires was hanging over the Great Lakes

when the Coburn began its trip from Duluth to Buffalo.

Second Mate W. L. Hanes, a survivor, said Demont was concerned

about the poor visibility and decided after nightfall to keep the steamer's engines in check and the boat was virtually parked

in one spot, somewhere in northern Lake Huron. Had the Coburn been traveling at good speed, it might have slipped past the

open waters of Saginaw Bay and escaped the brunt of the southwest gale that claimed her the following day.

The Coburn

was carrying about 70 people and a cargo of wheat, flour and barrels of silver ore. She followed the steamer Empire much of

the day, until the Empire stopped at Presque Isle on Saturday evening.

Passenger John Gray of Marquette, said the gale

was developing when the Coburn passed Presque Isle. He said that while other boats were running for shelter with all speed,

Demont foolishly ordered the Coburn to steam dead ahead into the storm.

Mate Hanes rebutted Gray's allegation. He said

the weather was fair and Demont had no thought of putting in when the ship passed Presque Isle harbor. By 10 p.m., however,

the wind was blowing fresh from the northeast and the ship was rolling heavily. There was so much smoke in the air that Demont

decided to turn the vessel's bow into the wind and check down the engines. The plan was to make the boat as comfortable as

possible for passengers and wait until morning when visibility improved before continuing on.

The storm hit them with

great fury out of the southwest a few hours later. The Coburn turned again into the wind, but things went from bad to worse

in a hurry. As the boat rolled the passengers became alarmed. Everyone was awake and dressed by 3 a.m. A lot of the passengers

were seasick.

Hanes

said the Coburn held her own until around 4 a.m. when somewhere off Thunder Bay, the rudder was lost and the ship turned so

that the seas were striking her broadside.

Hanes said he was standing watch in the wheelhouse when the rudder went.

"On working the wheel it revolved so easily that it was at once evident that something was wrong with the steering gear. At

first it was supposed that the chains had parted, but an investigation soon showed that the rudder was gone."

After

that, the seas started tearing the Coburn apart. The stack fell and crashed into the cabin area. Down on the main deck, barrels

of flour and silver ore broke loose and began smashing holes in the bulwarks. Water flooded the ship through the holes.

Hanes

said the cargo shifted to leeward and the vessel developed a serious list. Workers cut holes in the bulwarks and started throwing

cargo overboard.

Finally, while the Coburn lay heeled over to port at an awkward angle, a large wave rolled over her,

smashing open the fireman's gangway. By dawn everyone knew the battle was lost. Cascades of water rushed into the hold with

every wave. The Coburn was sinking.

As the vessel began her final plunge,

Hanes said the crew was making frantic efforts to launch lifeboats. Demont sent word to the passengers "to prepare for the

worse. But very few came out of their cabins. Most were sick and they did not care to make the effort to save themselves."

Hanes

said the two yawl boats were launched. He said he took seven people with him in one, and 10 others got in the second yawl

just as the ship slid stern first into the lake, literally dropping out from under their feet. The boats floated off the deck.

He said he didn't think any of the other boats got away.

Captain Condon said he saw a third boat launched before the

Coburn sank. He said he shared a boat with Thomas Durrin, John Bridgman, Spencer Churchwell, Henry Munford and John Young.

A second boat got away with about nine people aboard, and the third boat had about 15 people in it.

"A fourth boat

was on the davits, filled with people, and was being launched when the Coburn gave a heavy lurch and immediately sank out

of sight. The small boat filled with people was swamped, and we afterwards saw them in the water," Condon said.

"When

the Coburn went down, her upper cabin was burst off and we afterwards saw it floating away, covered with people.

"Before

the Coburn went down, I saw Captain Demont standing on the starboard arch, when a large wave struck him and threw him in the

lake. When he rose he caught a barrel that was floating near him, but he soon sank again and disappeared," Condon said.

Condon's

boat was picked up by the bark Robert Gaskin at about 4 p.m. By then the storm was abating and the seas were calm enough that

the rescue was not difficult.

Eight other survivors, including Hanes, were picked up by the bark Zack Chandler and taken to Mackinaw.

The third lifeboat, described

by Condon, apparently capsized. Two boats later drifted ashore at Kincaradine, Ont. One of them was empty and two bodies were

found either in or near the other boat. Bodies, barrels of flour and wreckage drifted ashore along the Canadian coast for

several days.

The exact location of the Coburn is not known.

|