|

|

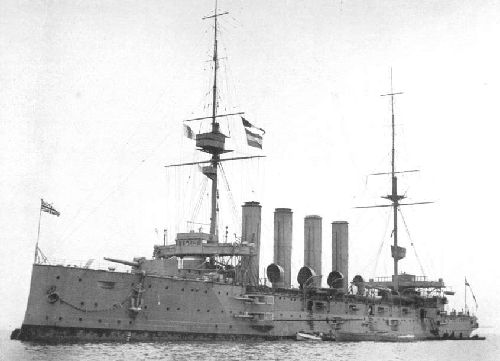

| Aboukir |

Sinking The Live Bait Squadron

By James Donahue

Even before it happened, the British Admiralty joked about the probability of Rear Admiral Henry H.

Campbell’s Seventh Cruiser Squadron was totally unsuited for its job of patrolling the high seas for German u-boats.

The big coal-burning steamers were secretly known as the "live bait squadron."

The time was September 22, 1914, and England was at war with Germany. Campbell’s squadron was

assigned to guard the entrances of the North Sea against u-boats, a task that the admiralty wanted to assign to other fleet

vessels as soon as possible. The nation was just tooling up for the war and there just weren’t enough naval ships to

do all that needed to be done.

On this particular day the weather was nasty and the big cruisers Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue were patrolling

the Broad Fourteens, an area between Yarmouth and the hook of Holland, known as Ymuiden, without destroyer escort. The flagship

of the fleet, commanded by Rear Admiral Christian, was the Euryalis. But as the squadron was preparing to leave the Euryalis

was forced to drop out for lack of coal and damage discovered in her wireless equipment. Thus the command was transferred

to Captain Drummond in Aboukir.

Now we have three tired old cruisers steaming North Northeast at a leisurly 10 knots. They were not

even zigzagging, as naval ships do in time of war, thus making it difficult for enemy submarines to fire torpedoes with true

precision.

Enter German submarine U9, with Captain Otto Weddingen in command. When he raised his periscope this

fine morning he could not believe his luck. There in front of him were three light British cruisers. They were lined up for

him like sitting ducks in a row. It was obviously a very stupid thing for Captain Drummond to have done.

|

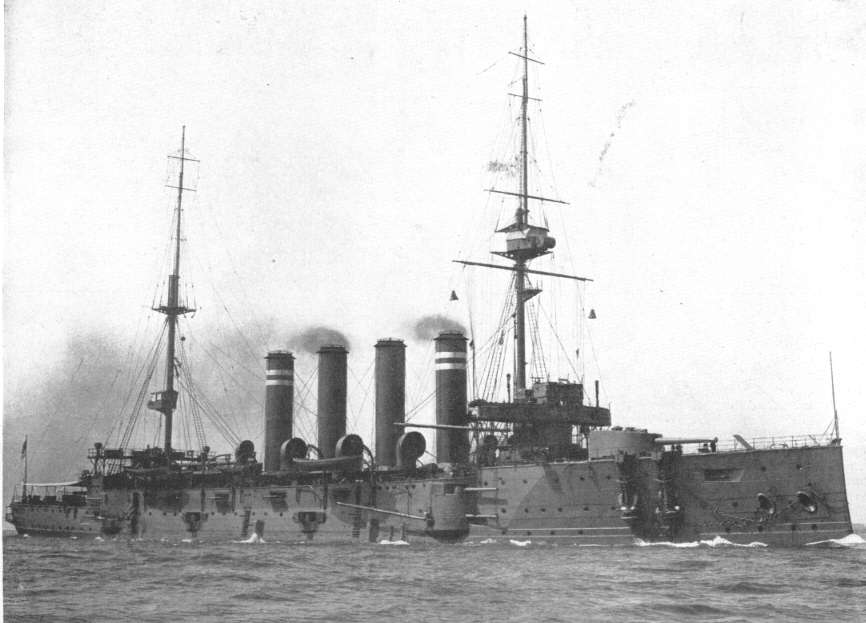

| Cressy |

The first torpedo struck Aboukir amidships on the port side. The old ship flooded quickly, took on

a 20 degree list and lost engine power. Captain Drummond did not realize it was a torpedo that struck his ship, but believed

he had struck a mine. This is where Drummond made his second big mistake. He ordered the other two cruisers to stand by and

pick up his crew.

In the meantime, as the Aboukir was sinking, the crew members found that only a single lifeboat had

survived the attack so men were jumping over the side and into the sea. The cruiser sank in 25 minutes taking 527 sailors

to the bottom with her.

As Aboukir rolled over and sank, Weddingen was lining his submarine up for another shot, this time

at the Hogue. This time he fired two torpedoes that struck the Hogue amidships and quickly flooded her engine room. Captain

Nicholson by now suspected a U-boat attack, but believed the sinking Abourkir was between him and the submarine. He determined

to drop boats and rescue as many men in the water as possible. Consequently Nicholson lost his own command.

|

| Hogue |

In those early years, German submarines were relatively small and they operated close to the surface.

The firing of two torpedoes affected the trim of U9 and the sub broke the surface of the sea for a few minutes. Gunners on

the Hogue had time to fire on the submarine, but they failed to hit it.

The gunners on that old cruiser didn’t really have a lot of time to use those guns. The Hogue

was so badly ruptured it sank in only ten minutes.

Now the Cressy, under the command of Captain Johnson, was in big trouble. Johnson had also stopped

his ship to rescue survivors. He ordered the ship underway when a periscope was sighted but it was too late. U9 fired two

more torpedoes. One of them missed but the second one struck Cressy on the starboard side, even as the ship’s gunners

fired on the spot where the periscope was seen.

The damage to Cressy was not yet fatal, but Weddingen turned around and fired his last torpedo. It

also struck Cressy and dealt a fatal blow. The steamer was sunk within the next fifteen minutes.

There were 837 men rescued by nearby merchant ships, fishing trawlers and other vessels that arrived

on the scene. Another 1,459 sailors perished in that single attack that lasted no more than an hour. It was a severe blow

for the Royal Navy just two months into the war.

In the aftermath, patrols by armored cruisers were abandoned, all major ships were ordered to stay

out of dangerous waters and all ships were under orders to steam at 13 knots and zigzag at all times while at sea. The engagement

proved the submarine as a powerful offensive weapon and it altered the conduct of surface warships during time of war forever.

A court of inquiry placed blame on all of the senior officers involved. Captain Drummond was criticized

for not zigzagging, Admiral Christian was criticized for not giving Drummond the authority to call for destroyer escort, and

Admiral Campbell was ostracized for not being present. Most of the blame was directed at the Admiralty for sending a patrol

like that into harms way when the senior officers knew better.

|

| U-9 Got Them All |

|