|

|

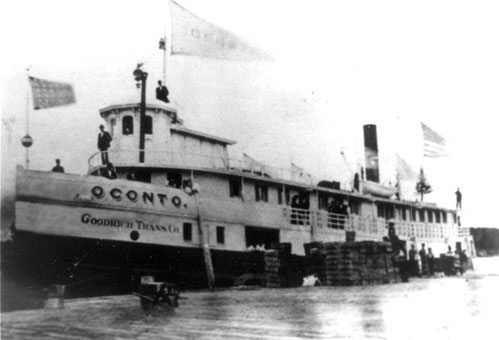

| Oconto |

Wrecked on Charity Island

By

James Donahue

Blinded by a fierce blizzard and hammered by wind and seas screaming across the open waters

of Lake Huron, the steamer Oconto was in serious trouble.

As the 47 sailors and passengers held on for their lives

amid tumbling furniture, wild running livestock that broke loose, and seas that were smashing the windows, doors and walls

of the wooden superstructure, Capt. G. W. McGregor used all of his skill to find refuge before his boat was lost.

It

was Dec. 4, 1885 and the Oconto was making its final trip of the season northward along the Lake Huron shoreline toward Green

Bay, Wis., where the boat was scheduled to lay up for the winter.

The storm struck after the Oconto left Oscoda on

what was to have been a short trip to Alpena. The gale grew in strength so fast, and the snow fell so heavily, that McGregor

decided to turn the boat around and run before the wind and find shelter at Tawas Bay.

First Mate Charles Rearden of

Port Huron told how he was called to the main deck after the horses and cows broke loose from their stalls and were running

at large. Before he got there, however, Rearden said he passed the galley and saw trouble there.

"The kitchen stove

was red hot and I thought the boat would take fire. I went to put this out first," Rearden said. That was when he found the

cook, William Brown, lying on his bed and crying for help. By the time he got the stove cooled down, Rearden said Brown was

dead. He apparently died of fright.

On the main deck, the mate said he found total chaos. One of the gangways was forced

open by the storm and he managed to get it closed. Horses and cows were tumbling and sliding around with the roll of the ship.

Many of the animals had their legs broken.

"Everything on the upper deck, including several cutters, one hundred chickens

and turkeys and hand sleighs were washed away. All four cranes broke. The cabin was badly broken up," Rearden said.

An

unidentified worker in the engine room told the Huron Times at Harbor Beach: "Our starboard bulwarks were stove in and all

the upper railings, two of the lifeboats and all of the light freight on the hurricane deck were washed away. The horses were

being thrown about, the cabin furniture went dancing in every direction and in fact, we were in the liveliest gale I guess

the boat ever experienced. The snow came so thick and fast that we couldn't see 20 feet away."

He said he and the chief

engineer were kept busy shutting off and turning on the engines with each wave just to keep the boat moving. The waves were

so high the propellers were being lifted completely out of the water, causing them to race erratically.

Captain McGregor

turned the boat northward into the wind in an attempt to stop the rolling until crew members got control of the livestock.

Later, as the storm intensified, he turned around again and made another attempt to reach Tawas.

Rearden said they

saw a light off the starboard bow and headed for it, thinking at first it was the light on Tawas Point. Later, as they got

close, McGregor determined the boat was approaching Charity Island, in the middle of Saginaw Bay. He realized by then, however,

that he was getting dangerously close and ordered the wheelman to turn the boat. But it was too late. The Oconto struck moments

later and stranded about a mile off shore.

"As soon as the boat struck the crew began dealing out life preservers,"

the unidentified story teller said. "There was no panic. Even the two lady passengers were very quiet under the circumstances.

One of them had a three-year-old child which steward (David M. Leary) wrapped in two heavy blankets and fashioned with a life

preserver."

The Oconto was made of good timber and it held together, in spite of the terrible hammering it took for

another two days.

"You can imagine what our feelings were when we found that she (the boat) wasn't leaking anywhere

and that even with our engines stopped, she held her position," the story teller said.

At daylight distress signals

were hoisted and five crew members went to shore in a metal lifeboat. The lighthouse keeper and his assistant launched a yawl

and before the day was out, they successfully had all of the passengers and crew members safely ashore.

Two days later,

after the worst of the storm was over, seven members of the crew, including the story teller, took the yawl back to the wreck,

recovered the compass and some provisions, and then pulled for Caseville, about 15 miles to the south.

Captain McGregor tried to persuade us

to give up the trip. We started in the midst of an ice cake and had to work every minute to keep from freezing. The spray

dashed over us and froze as it struck."

When about four miles off shore, the boat encountered solid ice. "We tried

to cut our way with axes. For six hours we cut, pushed, rowed and struggled like mad within sight of Caseville. At six o'clock

that evening we reached shore."

The wreck on Charity Island was not quite the end of the Oconto. The boat was raised in the spring, rebuilt

and made ready for one final disastrous trip.

The Oconto left Port Huron in the summer of 1886 with a cargo of dress

goods and silks, bound for Alexandria Bay, Lake Ontario. On the way, however, the boat collided with a dock on the St. Clair

River, then collided with a tug at Toledo. The steamer sprang a leak on Lake Erie and laid over at Cleveland for repair. Then

on July 6, the boat struck a rock on the St. Lawrence River and sank at Fisher's Landing in about 200 feet of water.

More Ship Stories

Return to The Mind of James Donahue

|