|

|

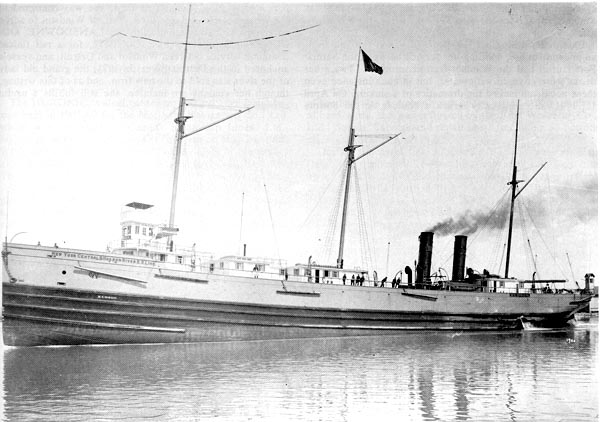

| Hudson |

The Haunting of Captain McLean

By

James Donahue

The date was Sept. 16, 1901. There was a storm raging on Lake Superior and the freighter John

M. Nicol was in trouble. The ship had been battling the fierce northeasterner for hours and the hull was leaking. The water

was seeping in so fast the pumps were not keeping up.

At about dawn, Chief Engineer George E. Tretheway called Capt.

William "Bill" McLean to the engine room to give him more bad news. He said the constant wrenching and twisting of the iron

hull was working on the pipes. The steam pipes were close to breaking open. "This boat can't stand the strain much longer,"

Tretheway warned.

McLean ordered the Nicol to steam hard for Michigan's Keweenaw Peninsula, hoping to get safely to

the lea of the land before his ship was lost. Everybody on the boat knew they were in a race against time. If he just got

close to the shore, McLean knew he had the option of running the boat aground just to save it from sinking. He and Tretheway

discussed this option when they talked that morning.

This was McLean's state of mind at about 10 a.m. when the Nicol

came upon the steamer Hudson in a sinking condition about eight miles off Eagle River. For the crew of the stricken Nicol,

this presented a terrible dilemma. The Hudson was caught in the trough of the seas, her engines obviously cold because there

was no smoke coming from the twin stacks, and the boat was listing hard to starboard. The seas were rolling over the sloping

decks and crew members were seen huddled together near the bow, clinging to the port railing.

It was obvious that the

Hudson had developed engine trouble, could not keep underway and fell off to the mercy of the wind and waves. Her cargo of

flax seed and wheat had shifted. By the time the Nicol came upon it, the Hudson was within minutes of foundering.

McLean

now had a hard decision to make. Should he attempt to rescue the crew of the Hudson and risk losing his own crippled vessel?

His decision was to save the Nicol and his own crew. It was a decision that haunted McLean for the rest of his life. He steamed

on into the storm, leaving the Hudson and its entire crew behind. By the time the Nicol arrived at Sault Ste. Marie two days

later, the captain was so shaken he could not stop explaining his actions.

"We passed within a half mile of her and

it was hard to go on and leave the men to their fate," he said. "It was out of the question to stop, however much the call

of humanity might demand it."

By the time he reached Detroit on Sept. 23, McLean was going to great lengths to justify

his actions. He told about the leaking steam pipes and the dash for safety behind the Keweenaw Peninsula. "It was a question

of staying away and having one boat and one crew go down instead of running close and having two boats and two crews drowned

in the storm," he said.

"We were leaking badly, had three feet of water in our hold and the seas were washing us from

stern to stem. We had two pumps and siphon working full blast, but still the water was gaining and there was 25 miles between

us and the nearest point of shelter. In order to render any assistance it would have been necessary to run to the lee of the

Hudson and get lines to the crew. To run to the lee of the Hudson would have meant to sink my own boat and sacrifice the lives

of the 21 persons aboard her.

"One roll of the Hudson against the Nicol would have sent her to the bottom in five minutes.

It was a terrible thing to see those men clinging there with not much chance in a thousand of ever getting away, and then

have to pass them. But it would have been fool hardy to attempt to run close to her," McLean said.

The Hudson was listing

so badly, it was theorized that her crew could not launch the lifeboats. McLean said the boats were still on the davits. Thus

it was that all 25 crew members on the ill-fated Hudson were lost with the ship. The dead included Capt. A. J. McDonald, first

mate Charles Brooks, second mate Bert Gray, chief engineer Moses Trouton, second engineer George Vogt and crew members, Donald

Glass, Peter Renning, Edward Miller, John Hughes, Heney Meyers and Neil S. Pearson.

Two regular crew members missed

the trip. Thomas J. Reppenhagen of Buffalo, the first mate, got Gray to replace him for the trip so he could be with his sick

wife. Wheelman Fred Peterson, who had been with the ship for seven years, decided for some unexplained reason to quit his

job before the Hudson sailed from Duluth on the last leg of its trip of no-return.

More Ship Stories

Return to The Mind of James Donahue

|